Big Boy

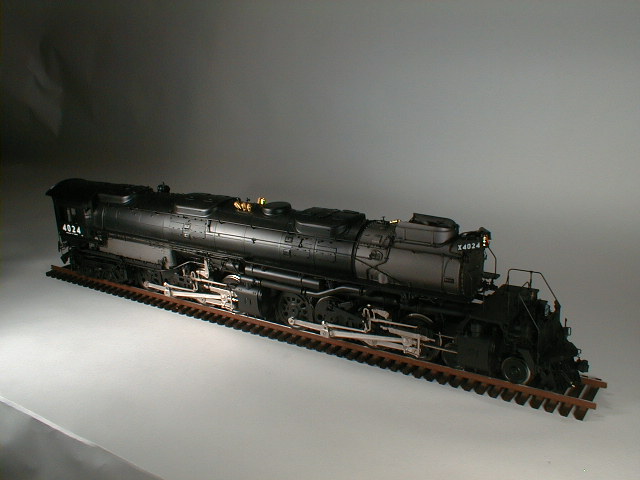

Union Pacific Big Boy – As Built

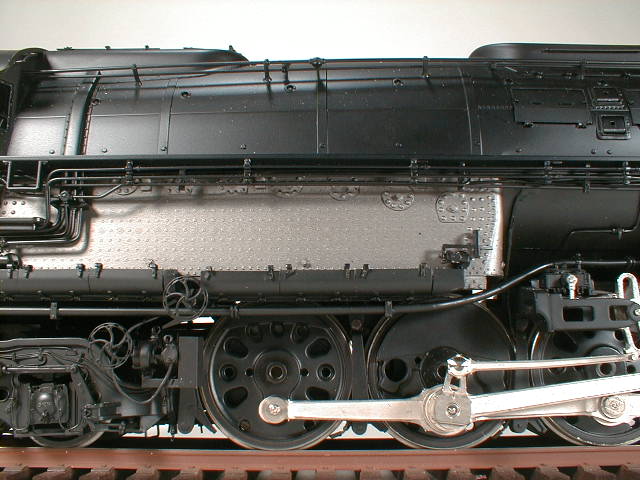

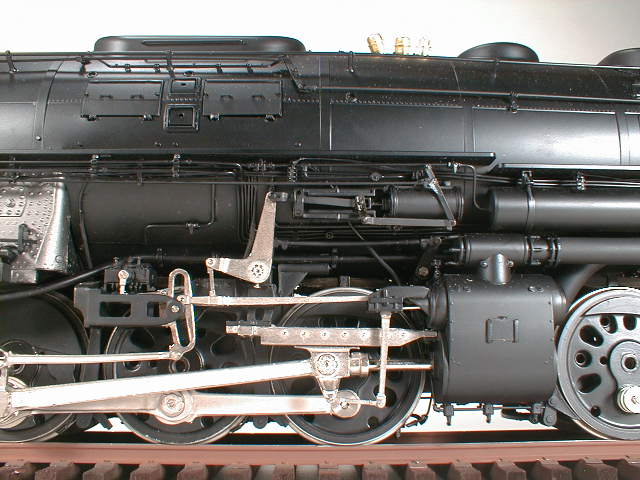

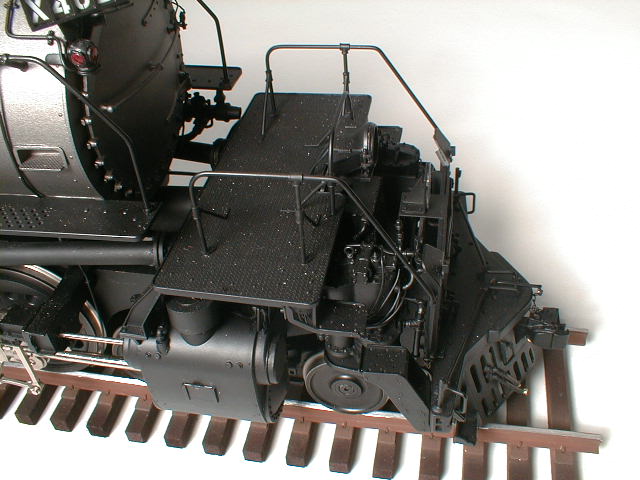

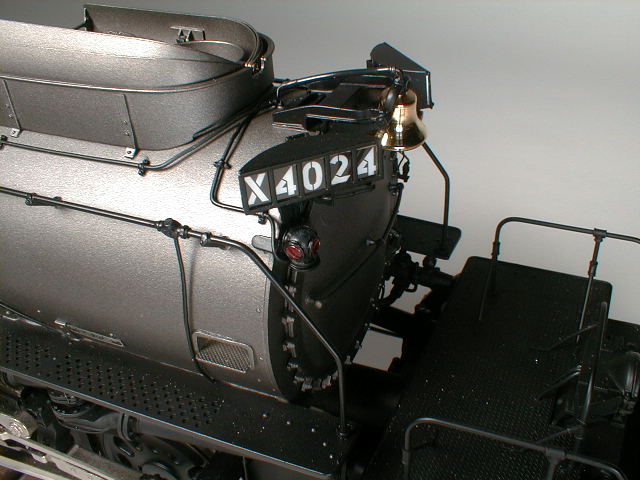

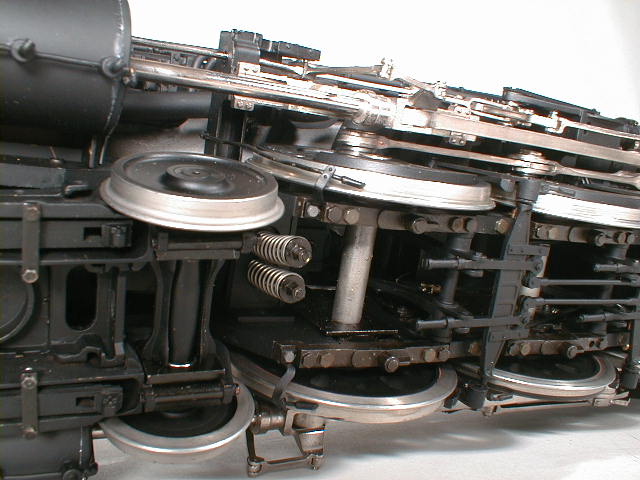

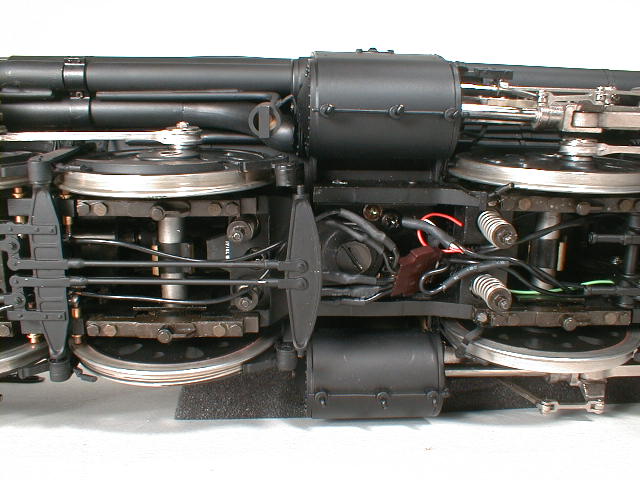

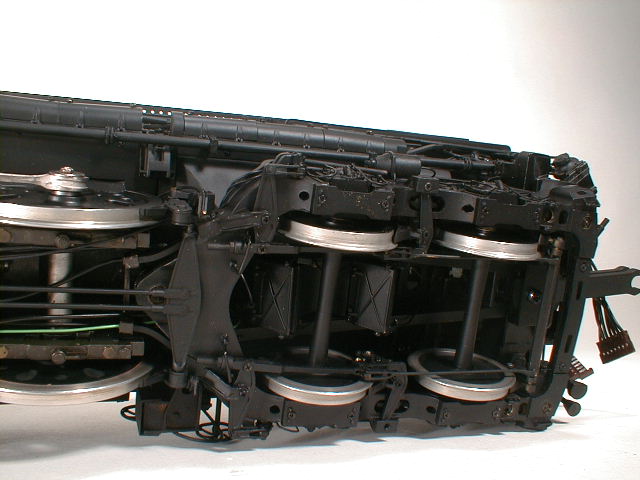

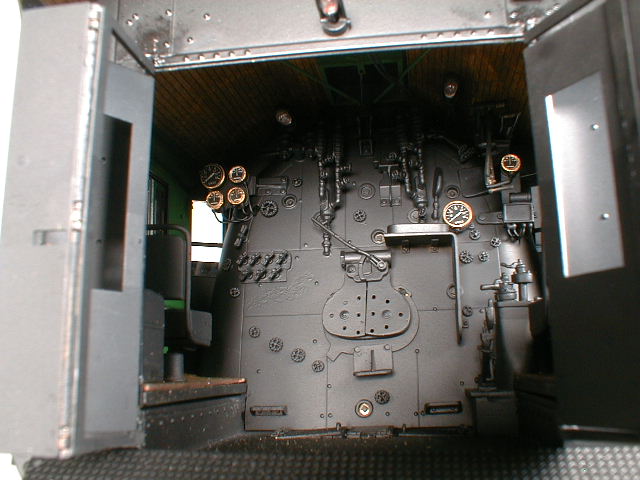

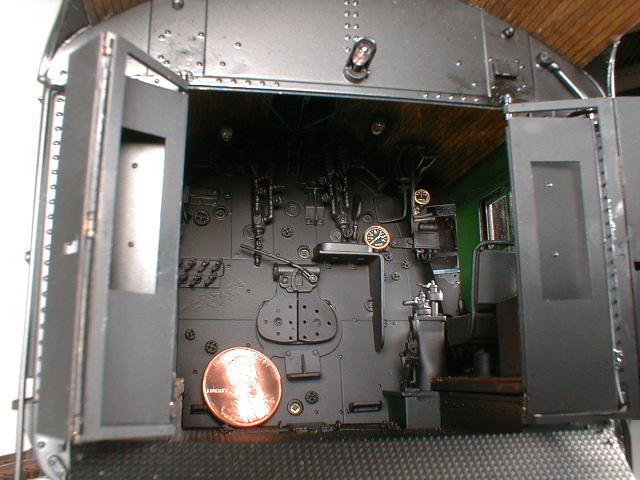

- Scale: 1:32

- Release: 2000

- Limited Edition: 50

- Model Size: 50”L x 5”W x 7”H

- Base Type: Black Walnut

- Base/Case Size: 56”L x 12”Wx 10”H

- Availability: Sold Out

Union Pacific Big Boy – As Modified

- Scale: 1:32

- Release: 2000

- Limited Edition: 50

- Model Size: 50”L x 5”W x 7”H

- Base Type: Black Walnut

- Base/Case Size: 56”L x 12”Wx 10”H

- Availability: Sold Out

Union Pacific Big Boy – 2nd Edition As Built

- Scale: 1:32

- Release: 2000

- Limited Edition: 25

- Model Size: 50”L x 5”W x 7”H

- Base Type: Black Walnut

- Base/Case Size: 56”L x 12”Wx 10”H

- Availability: Sold Out

Union Pacific Big Boy – 2nd Edition As Modified

- Scale: 1:32

- Release: 2000

- Limited Edition: 25

- Model Size: 50”L x 5”W x 7”H

- Base Type: Black Walnut

- Base/Case Size: 56”L x 12”Wx 10”H

- Availability: Sold Out

Union Pacific Big Boy

Surely the most famous steam locomotives of all were the Union Pacific’s Big Boys. “That such a vast steam generating plant could be mounted, not on concrete and clothed in brick, but on a flexible base which rode comfortably at 50 miles per hour … these circumstances will be remarked upon as long as men gather to talk of steam and steel,” wrote the late Trains Magazine editor David P. Morgan.

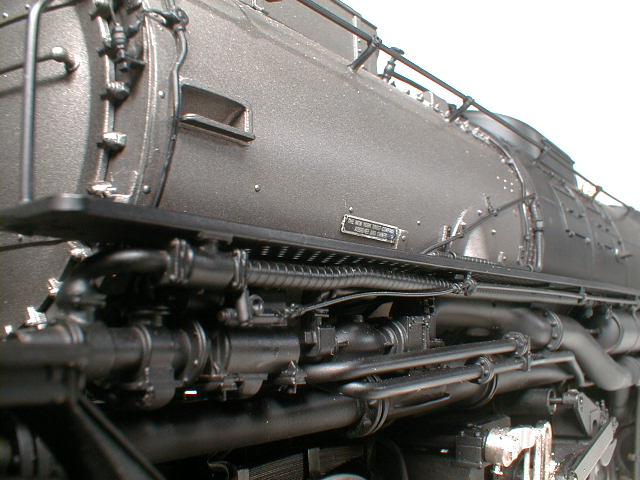

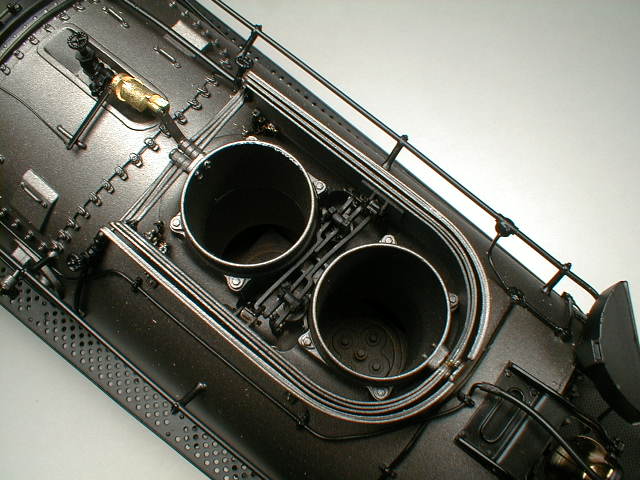

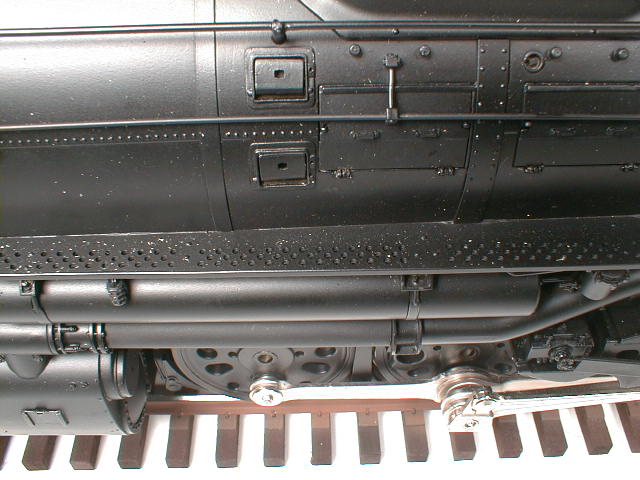

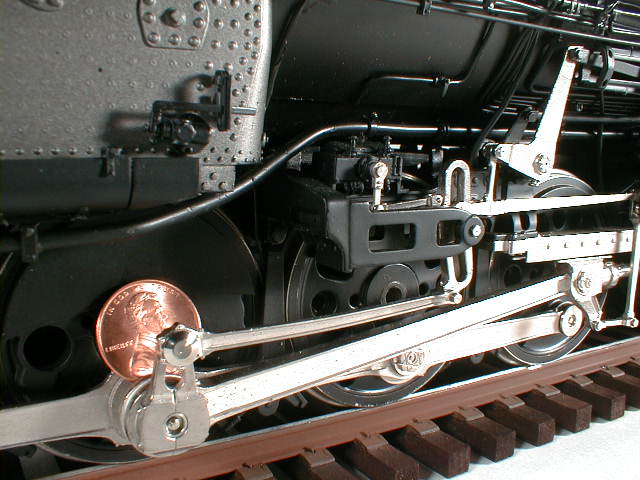

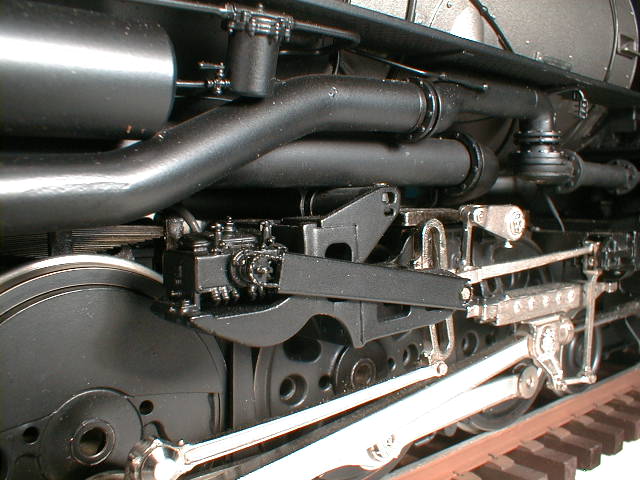

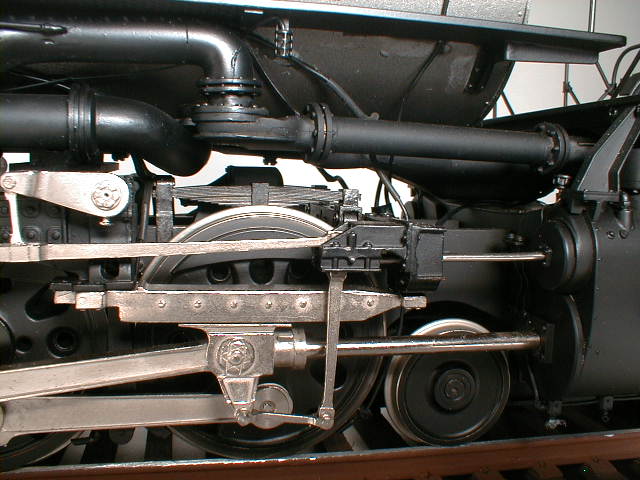

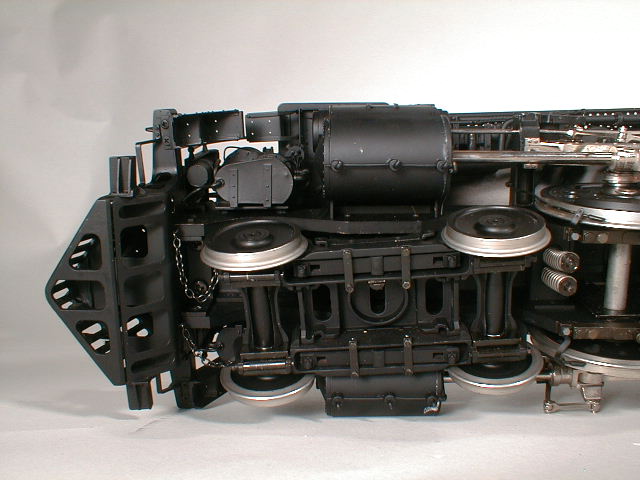

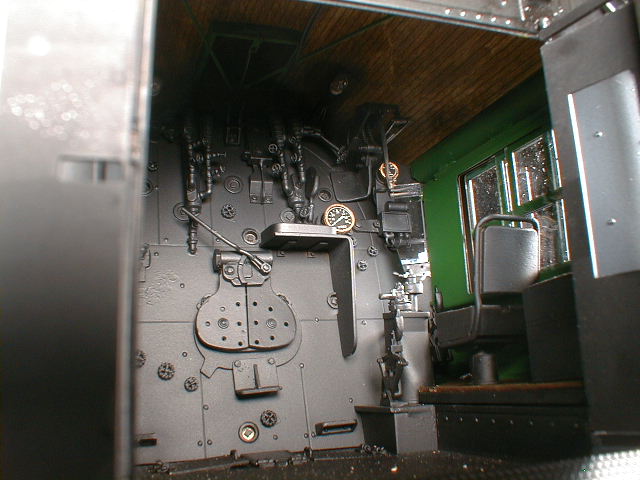

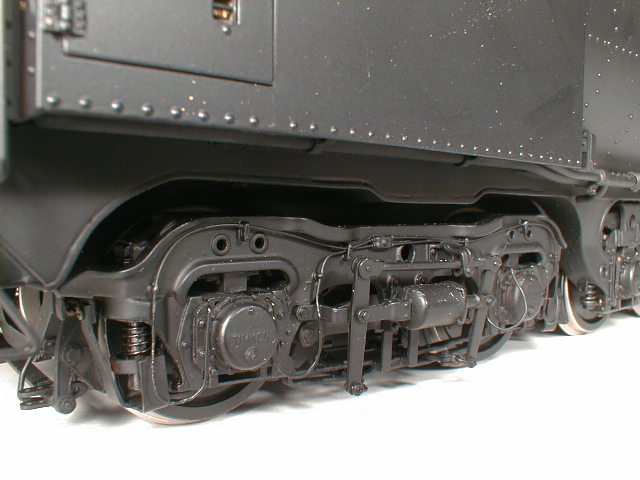

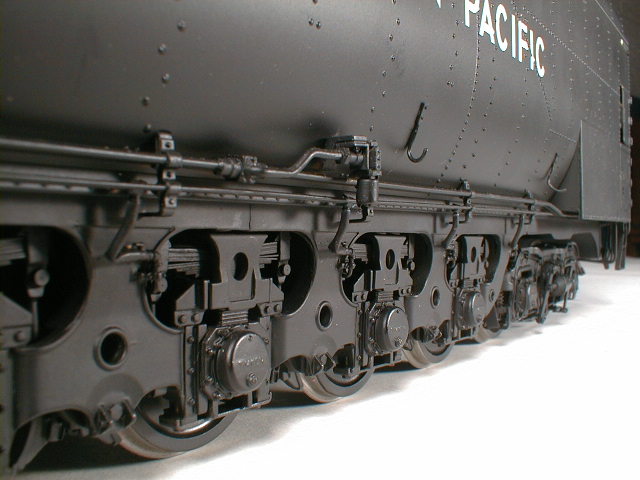

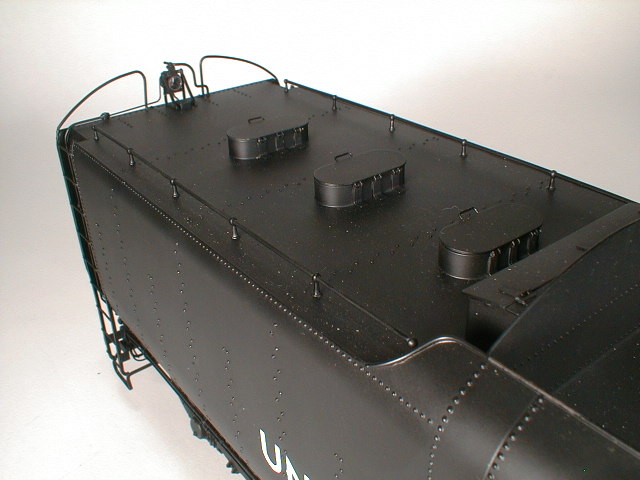

The Union Pacific—America’s first transcontinental railroad—has always been in the business of hauling heavy trains at speed over long distances, and has always had a need for a fleet of the largest, most modern locomotives. But in 1940, as the depression eased and with the coming of war, it lacked a locomotive that could both pull on mountain grades, what its existing locomotives could pull on the flat, and sustain speeds over 50 miles per hour. Vice President Otto Jabelmann’s mechanical staff calculated that it would take an engine with 135,000 lbs. of starting tractive effort to pull 3,600-ton trains, unassisted, up the 65-mile Wasatch grade east from Ogden, Utah—the toughest climb on the Overland Route. Such an engine would, of course, require a giant boiler and huge grate area (the railroad’s own coal lacked the high heat content of the coal available to the eastern coal-haulers), but these would easily provide the 540,000 lbs. on drivers, it needed for adhesion. To spread the locomotive’s estimated total weight of 762,000 lbs. without excessive axle loading, a 4-8-8-4 was recommended.

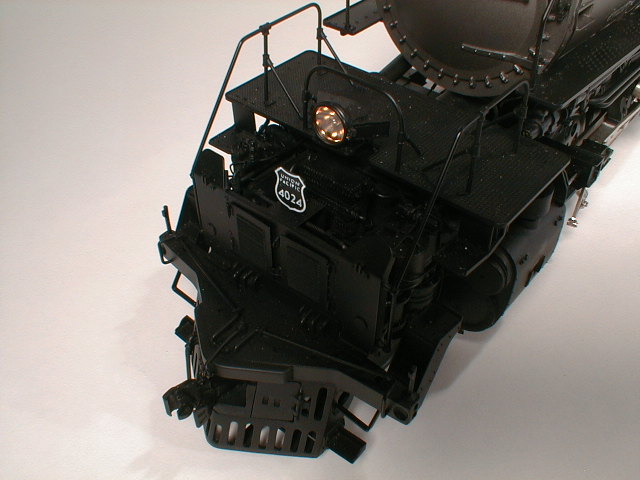

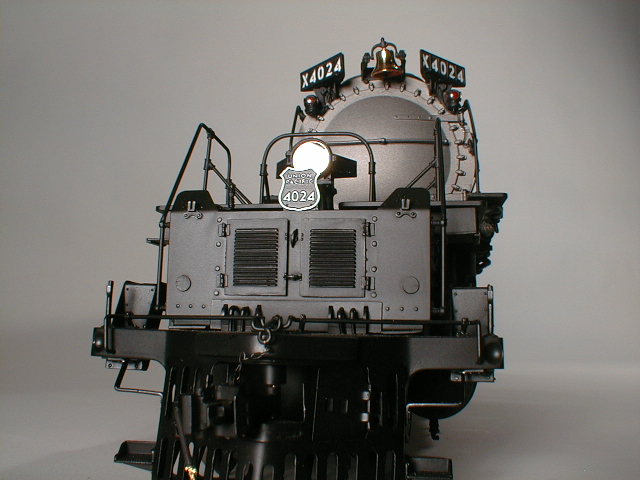

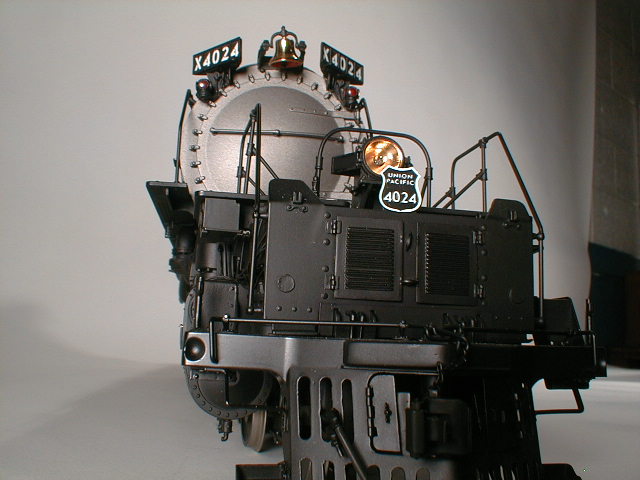

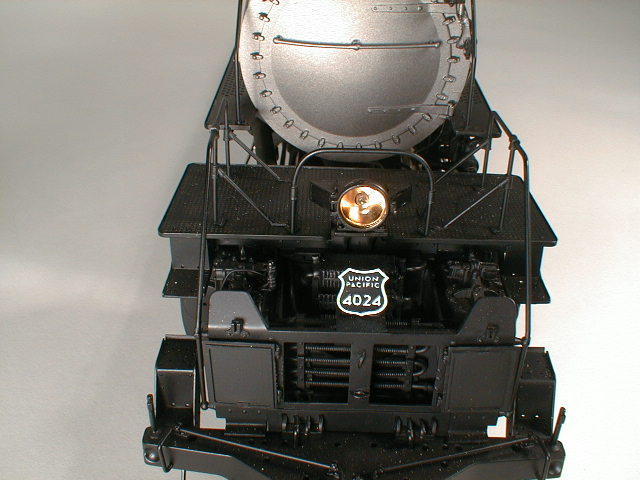

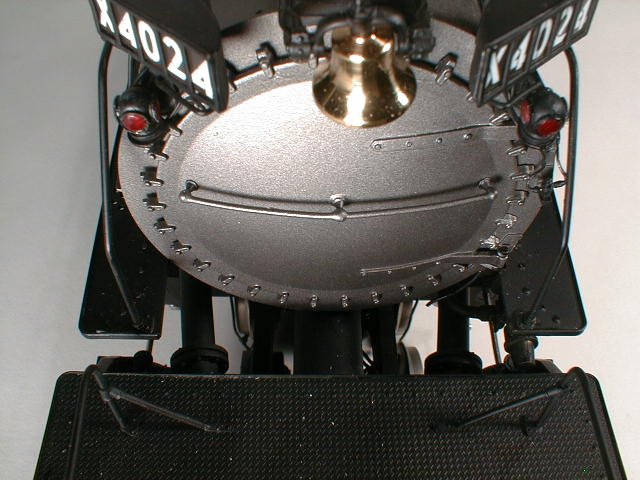

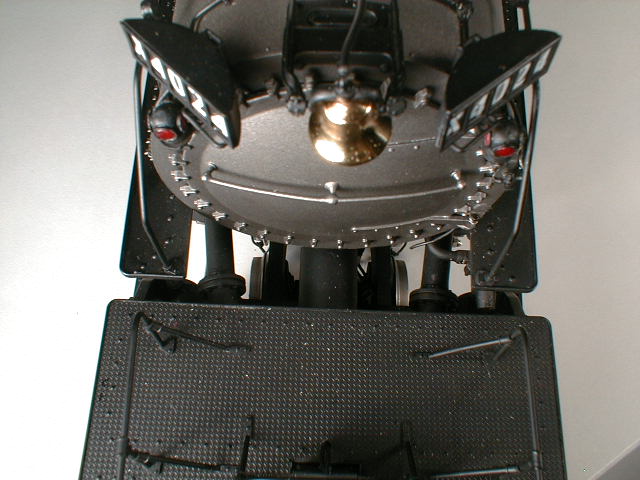

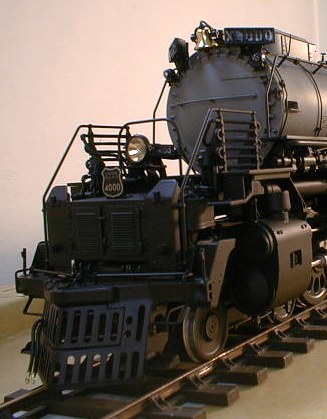

The resulting 4000-class locomotives were known from the start as the world’s largest. Before No. 4000 received its final painting, a mechanic at the American Locomotive Company in Schenectady, New York scrawled the words “big boy” in chalk on its huge smokebox door and soon the railroad was using this name to publicize the locomotives. UP President Arthur E. Stoddard, “Boss of the Big Boys,” called them “the greatest engines I had seen.” More than the tools of an era, they were a symbol of the finest in transportation.

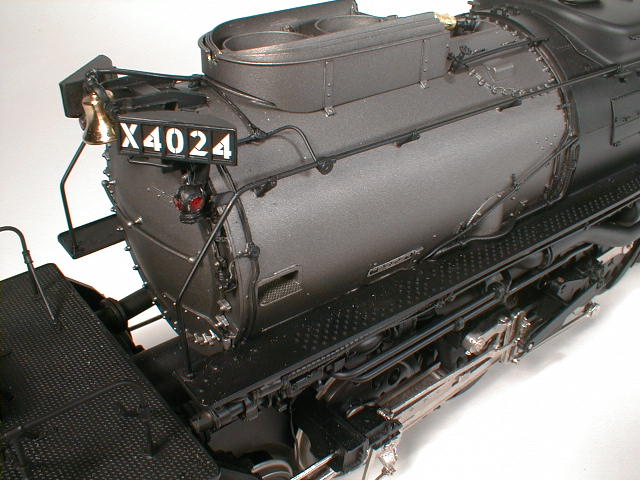

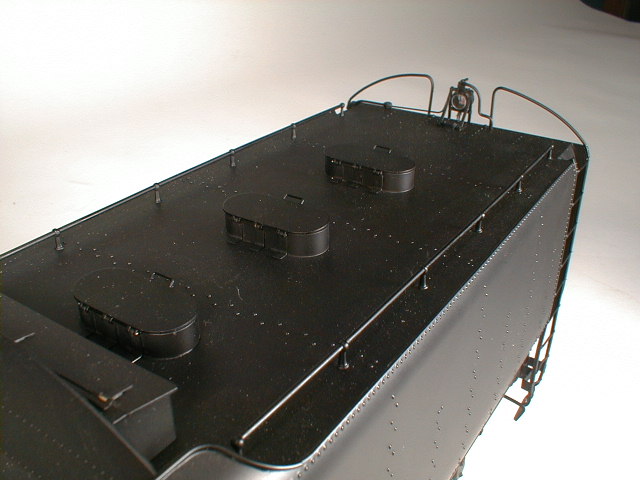

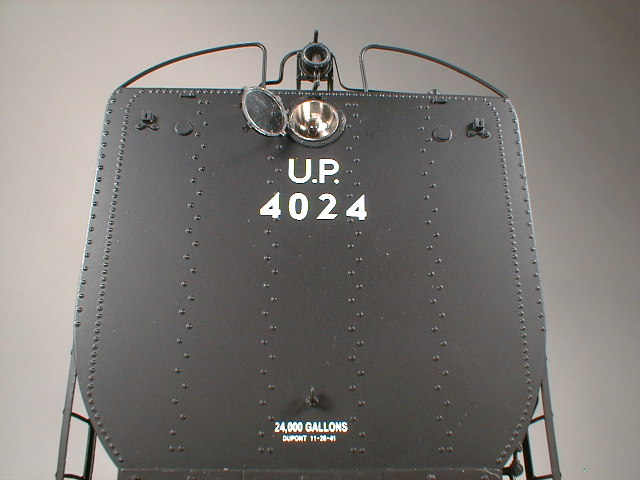

Twenty-five Big Boys were built into two groups: Nos. 4000–4019, later designated 4884-1, were delivered beginning in September 1941. Nos. 4020–4024, designated 4884-2, followed in 1944 to handle the transcontinental traffic boom of late World War II. Both groups went to work on the Wasatch where, in later years, after millions of miles of service, the railroad increased their rating to 4,450 tons. Their boilers could evaporate 200 gallons of water per minute, so they needed frequent water stops when hauling heavy trains. Yet they could be serviced in as little as an hour and could make 7,000 miles per month. On test, one recorded 6,290 drawbar horsepower.

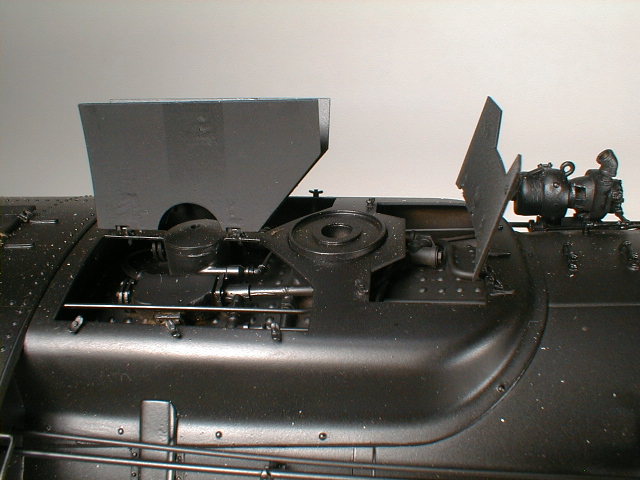

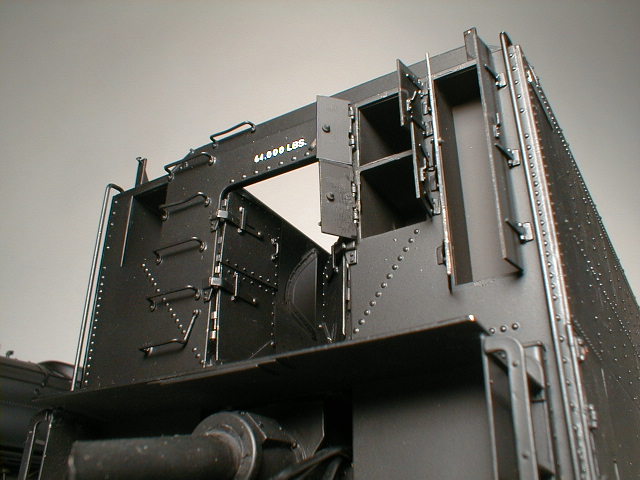

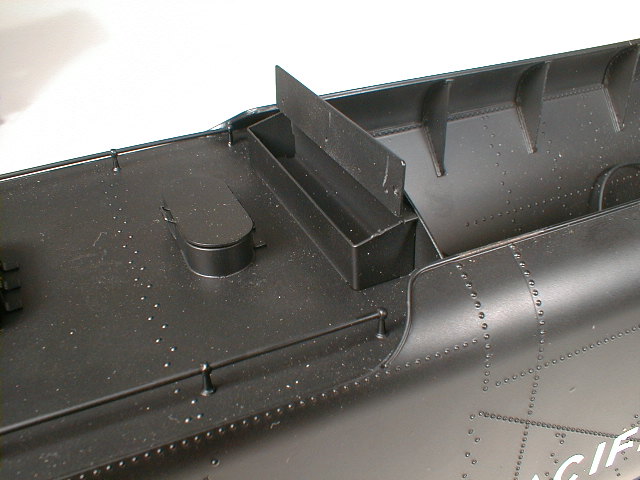

There was one conspicuous difference between the two groups. As built, the 1941 engines had fin after cooler piping (part of the air brake system) mounted high on the pilot deck. The 1944 engines arrived with these mounted behind the air pump shield to reduce icing (the UP modified the first engines to follow suit in 1948–52). There were other, more subtle differences of course. Alloy steel was used wherever possible in the 4884-1s, but medium-carbon steel was substituted in the 4884-2s, due to wartime restrictions. As a result, these were heavier — at 772,250 lbs. for the locomotive in working order, and more than 1.2 million lbs. with tender. Nos. 4020–4024 rank with the C&O’s first Alleghenies as the heaviest steam locomotives ever built.

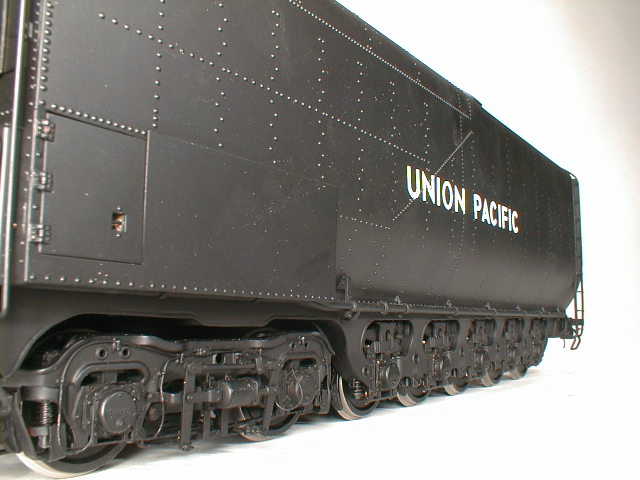

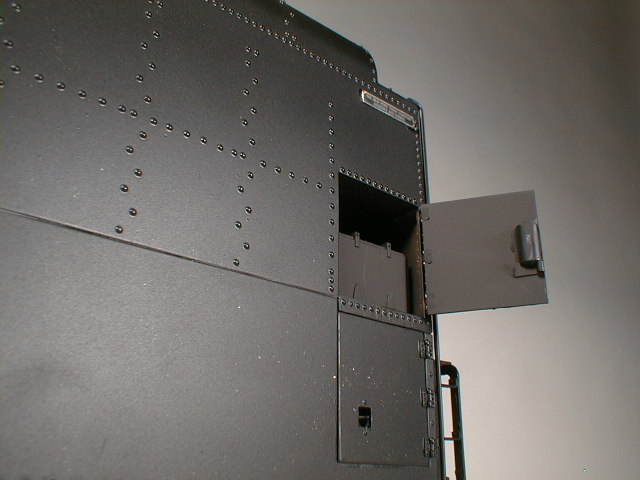

The Big Boys’ extended proportions made them look big—while other railroads owned locomotives with eight driving axles, none had drive wheels as large as the Big Boys’ 68 inches, nor a four-wheel engine truck out front to guide them into curves at high speeds—and they were big. With an overall length of nearly 133 feet for engine and tender, they required the Union Pacific to build three new 135-foot turntables, realign several curves for adequate clearance on adjacent tracks, and make other improvements. The Big Boys’ 300 psi boiler pressure and roller bearings on all axles represented the state-of-the-art. They ran wonderfully well so there was little need for experimentation. After World War II, 4005 was converted to oil, but the burner caused uneven heating and leaking, and was soon removed. In addition, elephant ear smoke-deflectors were mounted on 4019 in 1949, but for only a few runs. About the same time, however, steel coal boards were added to the tenders to increase coal capacity by four tons (this feature became permanent).

The Big Boys continued in operation for nearly 18 years, and all, of the first group, accumulated more than 1,000,000 miles before retirement. They worked all their lives in Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and very occasionally, into Nebraska. They were well maintained until nearly the end—twenty-three were shopped as late as 1957—and six of them were still active into the early summer of 1959 out of Cheyenne, the Mecca of steam. Today, eight of them are preserved: No. 4004 in Cheyenne, No. 4005 in Denver, No. 4006 in St. Louis, No. 4012 in Scranton, PA, No. 4014 in Pomona, CA, No. 4017 in Green Bay, No. 4018 in Dallas, and No. 4023 in Omaha.